- Current Events Democrats Respond to the President’s State of the Union

- Elections The Election Question: To Centralize or Not to Centralize

- Elections Who Will Be Iowa’s Next Governor?

- Current Events A History of the NATO Alliance

- Current Events Some Face Rising Health Care Costs

- Current Events Litigating the Separation of Powers

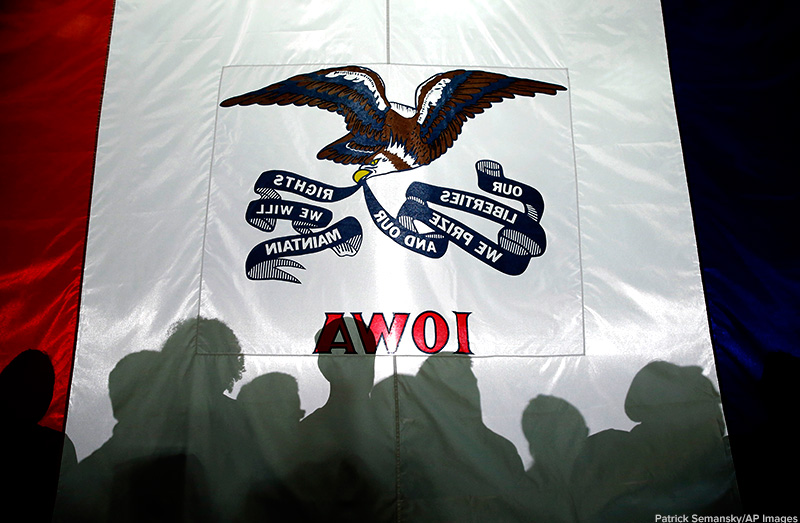

All Eyes on Iowa

In an era when election coverage includes sarcastic Tweets, and election-cycles begin earlier and earlier because of a candidate’s FOMO, our political traditions are getting turned on their heads. This includes the Iowa caucus, which will wrap up next week on February 1. In this post Election Central breaks the caucus down for you—past, present and future.

A Brief History

Click the book image to learn more about caucuses in the networks textbook, United States Government: Our Democracy.

In the early days of our country’s election history, presidential candidates were selected by a “Congressional Congress.” In other words, only the members of Congress chose the party’s nominee. State primaries and caucuses followed, but public participation was minimal, as the political party leaders in each state held closed-door nominating sessions. Primaries and caucuses serve the same purpose—to determine a party’s candidate for the general election. The difference is in the way votes are cast: Primary = private, caucus = public. Each state is allowed to determine which type it prefers.

Political reform in the early 1900s emphasized many different goals, all with the aim to democratize the political process. But it still took a while for primaries and caucuses to be taken seriously, and not just a way to “test out” a candidate’s popularity. Voter frustration came to a head at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The combination of anti-Vietnam sentiment and the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert Kennedy, generated violent public protests. Congress responded by creating the Congressional McGovern-Fraser Commission to develop new rules and guidelines to create more democratic elections. These new structures were implemented in the 1972 presidential election.

How Does A Caucus Work?

The process can vary from state to state and from political party to political party. In Iowa, voters are divided by precincts (there are 1,681 of them). The precinct voters gather at their assigned location (often a community center, church, school gymnasium, or sometimes a home). Republicans gather to hear speeches and then write their vote on a piece of paper. Democratic voters are physically counted while standing in an area designated for a particular candidate. (“Undecided” has its own designation.)

Candidates that fall below 15 percent of the vote are removed from consideration and their supporters, plus the undecided group must choose another candidate. Voters persuade one another to switch until there are only “viable” candidates left. Unlike the general election, votes are not tabulated by the state elections office but reported directly to the state party, which then reports the outcome to the media.

What About The Iowa Impact?

The Iowa caucus is significant, not because it closely represents the national population. It’s impact lies in the fact that it is first. (There is even state legislation that states that the Iowa caucuses must always be first.) There are critics who argue that the Iowa caucus has become little more than full-court press campaign gimmicks with little focus on actual governing or policy discussion. Others say that the event can reveal meaningful insights into a candidate’s strengths and weaknesses. Some believe that the process makes politicians work harder for votes and allows underdog candidates a chance to connect with voters in a more intimate way and gain the 3Ms—momentum, media and money.

Perhaps the biggest Iowa success story was Jimmy Carter. He is credited for transforming what a grassroots campaign can achieve with little money or attention and go on to win the presidency in 1976. On the other hand, former president Bill Clinton’s 1992 Iowa campaign put less of its effort in Iowa because, Iowa’s own senator Tom Harkin, was predicted to do well. And Clinton went on to win the White House without a strong Iowa showing.

Related Links

If you want more perspective on the Iowa caucus and some more perspective on Iowa’s political impact, listen to this podcast from NPR’s Fresh Air interview show. You can read a transcript of the interview from this link if you don’t want to listen to the audio.